本文是一篇英语论文,笔者认为译者的主体性是主动性和被动性的结合,这种结合是动态的和多样的,因为不同的交际行为导致不同的翻译风格。第四章从交际行为理论的角度对《夏洛特的网》四个中译本中译者的主体性进行了分析和描述,并对这四个译本进行了全面的评价。

Chapter One Introduction

1.1 Research background

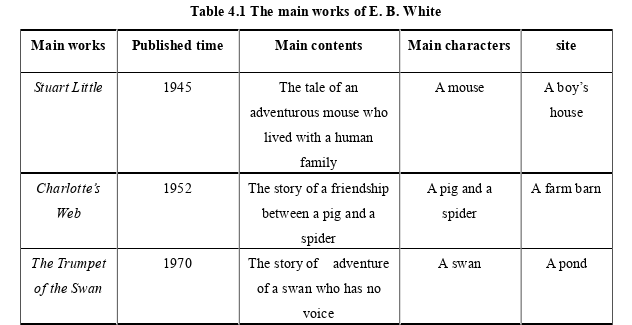

The development of translation studies accelerates the displaying of the translator’s subjectivity. In the west, Eugene Nida, George Mounin, J. C. Catford, and Roman Jacobson see the translation as a linguistic activity aiming to reach a level of equivalence. Accordingly, the task of the translator is to transfer message from the Source Language into the Target Language. In 1928, Benjamin (2000) puts forward his translation theories in his article The Task of the Translator, in which the concept of originality and authorship are primarily modified. Then Susan Bassnett (1998) points out that the concentration of translation study in the 1970s and 1980s turns to history and power, and the keyword of translation studies in the 1990s is “visibility”. Under the circumstance of the “culture turn”, the deconstructionists Venuti and Douglas lay great emphasis on the translator’s part in translation.

In ancient China, translation is looked down upon and regarded as parasitical and secondary art. At that time, the translator is regarded as a tongue man, or a imitating officer who transmits the word. In 1984, Luo Xinzhang summaries the traditional translation theory system as semantic equivalence, faithfulness, spiritual resemblance, and transmigration. Under this circumstance, the role of the translator is changing gradually. These theories make translators have even more freedom in translation to exert their creativity and subjectivity.

1.2 Research objectives

The thesis attempts to conduct a social philosophy-based analysis to make a descriptive and explanatory study of the translator’s subjectivity on the four Chinese versions of Charlotte’s Web. Bearing this in mind, this study is carried out:

1) To test the hypothesis that in translating the translator chooses the style of the Target Text based on the communications with other subjects.

2) To provide a new understanding and shed light on the study of the translator’s subjectivity.

3) To propose a philosophy-based and replicable model for the evaluation of the translated version in literary translation.

Chapter Two The Translator’s Subjectivity: the State of the Art

2.1 The changing status of the translator

Translation activities have a long history in human society. The translator, as an important participant in translation, has been playing a significant role in connecting different languages and cultures. For a long time, the translator’s role has been marginalized. Many derogatory names for translators such as a painter, an imitator, a camera and a copy machine (Ge, 2006) reflect the inferior status of translators. Translators’ painstaking efforts have not been given due respect and recognition until the “culture turn” in translation studies. In the following, the author provides the general review to describe the role of the translator in the major approaches of translation studies. It is also the developing process of the translator’s subjectivity.

The traditional translation theory focuses mainly on the fidelity which emphasizes the comparison between the Source Text and the Target Text. It requires the translator to be faithful to the Source Text author. The author is the master while the translator serves as a faithful slave subordinated to the author.

In the west, the earliest translation could be traced back to the Bible translation. The translator is required to be faithful to the Source Text and do the translation cautiously. Otherwise, a few deviations might cause misfortune. In the medieval age, Manlius Boethus claims that “translation should focus on the objective facts and translators should give up his subjective judgment in translation.” (Tan, 2004, p. 43) John Dryden of the 17th century used the word “slave” to name the translator, which means that the translator is the slave of the Source Text author. And other translation critics, such as Charles Batteus, George Steiner, Valery Larbaud and Monnan Shapiro all describe the translator as the servant, the shadowy presence, the beggar at the church door, and the invisible man respectively. (Tan, 2004) According to them, the translator should always strictly follow the Source Text faithfully and subordinate himself to the Source Text author.

2.2 Definitions of subject and subjectivity in translation

The “Subject” derives from the Latin word “subjectum”. It has “object” as its anatomy. Aristotle first defines that “a subject is an observer and an object is a thing observed”. Based on the previous studies, it has been made clear that the “subject” is the undertaker of an action, and the “object” is the receiver of an action. According to this definition, the subjectivity refers to the natural characteristics of a subject, namely the “individual interpretations of experiences consisting of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual perceptions and misconception” (Solomon, 2005, p. 900). In other words, the subjectivity refers to the individual’s self-determination, dynamic, and creativity.

It is universally accepted that translation is a complicated activity with various roles involved. When translating, the translator must first understand the Source Text before transforming the meaning of the Source Text to the Target Text readers. During the whole process, the translator is also the reader of the Source Text, attempting to understand the referential and implied meaning, and meanwhile the translator plays the role of the author of the Target Text, trying to make the Target Text readers have the same reaction to the Target Text. In this way, the Source Text author acts as the subject only in the process of the translator’s understanding, and the Target Text reader is the subject only in the process of the Target Text’s acceptance. It is the translator that takes part in the whole translating process, acting as the most active subject in understanding and interpreting. Based on this, this thesis selects the translator as the study object to further explore its value.

Chapter Three The Theoretical Basis and Research Data........................ 16

3.1 Habermas’ Theory of Communicative Action............................ 16

3.1.1 The communication rationality................................. 16

3.1.2 The consensus of truth............................... 17

Chapter Four The Translator’s Subjectivity in Light of the TCA on Four Chinese Versions of Charlotte’s Web....................... 26

4.1 Constraints: the rightfulness claim in the social world ........................ 26

4.1.1 The translator and the Source Text author ............................. 27

4.1.2 The translator and the Target Text readers ........................... 29

Chapter Five Conclusion .....................................51

5.1 The evaluations of the Chinese versions of Charlotte’s Web................................51

5.2 Rethinking the translator’s subjectivity.....................54

5.3 Limitations of the current research and future studies..........................55

Chapter Four The Translator’s Subjectivity in Light of the TCA on Four Chinese Versions of Charlotte’s Web

4.1 Constraints: the rightfulness claim in the social world

A Translation takes place in certain social and historical background, which requires communication to meet the demands in empirical world. A set of general rules and normative claims are prescribed to regulate the subject’s action. Under this circumstance, observing the rightfulness claim is the obligatory task for communicative subjects to reach consensus. The rightfulness claim asks translators to establish rational interpersonal relationship in the social world, developing inter-subjective consensus with all other subjects involved.

In translation, there are a number of different subjects, and the position of these subjects is equal. Apparently, the role of the translator lies in the center of translation. At first, the translator should have a frank conversation with the Source Text author to investigate the culture backgrounds and life experience so that the Source Text author’s intention and the meaning of the Source Text can be acquired. Secondly, facing the Target Text readers, translators build up equal dialogical relations for different readers and strive to achieve his translation purpose. At last, in shaping the characters of the Source Text, the translator should respect the norms of Target Language, namely interact with the patronage, and other translators for mutual understanding. In short, the translator should thoroughly grasp the reciprocal relations in the social world and handle them flexibly in translation. If the translator fails to conduct interactive relationship with the subjects in the social world, the rightfulness claim cannot be reached and it may leads to unacceptable translation.

Chapter Five Conclusion

5.1The evaluations of the Chinese versions of Charlotte’s Web

In translating Charlotte’s Web, each of the translator aims to reach the validity claims in the “life world”, in order to achieve the mutual understanding with the other subjects in the translation activity, including the Target Text readers, the Source Text author, the patronage, and the other translators. On the one hand, the communications are the process for translators to show their subjectivity. On the other hand, the translator is constrained by the other subjects in the communications. So the translator’s subjectivity is the combination of initiative and passivity, and the combinations are dynamic and various because different communicative actions result in distinctive styles of translations. By means of analyzing and describing the translator’s subjectivity from the perspective of the Theory of Communicative Action in the four Chinese versions of Charlotte’s Web in chapter four, here we present an all-around evaluation of the four versions.

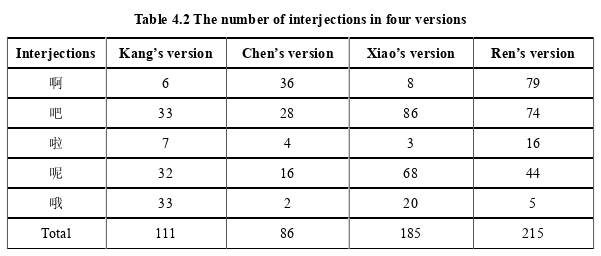

From the analysis of the Target Text style, we can evaluate the four versions as follows. The overall structure of Kang Xin’s version is unabridged. At the phonological Level, comparing with other versions, the number of the calculation of interjections, er-suffix is the least, which shows that Kang does not pay much attention to the tone of the sentence. At the lexical level, Kang’s chapter titles are more concise and faithful to the features of the Source Text, some choices of words in translation are relatively formal, and other content words conform to the corresponding social background and people’s habitual use. At the syntactic level, Kang employs many passive sentences in translation. Kang’s sentence structures are not idiomatic to some extent though she simplifies the long sentence and uses reiterated words sometimes. At the rhetorical level, the rhetorical devices used in Kang’s version is the most, and Kang often translates the phrases to four-character idioms, which makes her version elegant and beautiful. The obvious characteristics of Kang’s version are the words and four-character idioms.

reference(omitted)