Chapter One Introduction

1.1 Research Background

In the wake of acceleration of globalization, the international communicationbecomes increasingly frequent. In order to ensure the successful exchange ofknowledge and information, there is a great need of global language that can break thecommunicative barriers between countries. Due to the great influence of Americanand British economy and culture since the 19thcentury, English has been widelyrecognized as an international language and plays a role in tourism, business,computing, diplomacy and science (Graddol, 1997; Crystal, 2003).In its role of an international language in scientific world, English has becomethe most significant medium of academic communication and been established aslingua franca of scientific communication with nearly 60% of world’s scientificproduction in English (Weill & Weill, 2006). In this view, a good mastery of effectiveEnglish writing skill is a prerequisite for scientific writers, especially non-nativeEnglish writers, to participate in the international research communication andachieve professional success. The conventional format IMRD (Introduction, Method,Results and Discussion) of scientific writing provides writers with a standard modelof structuring their research articles and each section has its linguistic and structuralnorms. Among these sections, introductions are known to be troublesome and nearlyall academic writers admit to having more trouble in getting started on a piece ofpaper than they have in its continuation (Swales, 1990:136). Meanwhile, introductionsare the first impression writers leave on their target readers and influence readers’decision on further reading. Due to the above two reasons, it is not surprised to notethat during the past thirty years, there has been growing interest in the linguisticfeatures (Lackstrom et al, 1997; Oster, 1981; Swales, 1990; Hyland, 1998b.

……….

1.2 Research Significance

Generally, the subject matter of this study is to explore the use of hedges in SRAintroductions. The research findings would enrich the literature of research on EAP(English for academic purpose). To be specific, this thesis is of both theoretical andpractical significance.The research can contribute to enrich the literature on the approach to hedges inacademic settings. Essentially, the generation of scientific hedges is a dynamicprocess, involving target readers’ active roles in negotiating with writers to constructscientific claims. A successful scientific claim depends on the smooth communication,in which writers choose appropriate hedging strategies to create conditions forpersuading readers of their statements (Hyland, 1998a). In this view, the use of hedgesis a process of making-choice, motivated by writers’ intention to persuade targetreaders. The perspective of treat hedges as the result of making choice is consistentwith Verschueren’s (1999) theory of linguistic adaption. Verschueren (ibid) argues thatthe use of language is essentially a process of making negotiable choice, affected byvarious contextual factors to satisfy communicative needs. This theory, therefore,offers a new pragmatic approach to investigating hedging phenomenon from a generalpragmatic perspective.

………

Chapter Two Literature Review

2.1 Definition and classification of hedges

The notion of hedges is first introduced as a linguistic term by Lakoff. In hisarticle “Hedge: A Study in Meaning Criteria and the Logic of Fuzzy Concepts”,Lakoff concentrates on the logic properties of such words and phrases as rather,largely, in a manner of speaking, very, in their ability, “ whose job is to make thingsfuzzier or less fuzzy” (1972:213). Following Lakoff’s main concern, Brown andLevinson (1987:145) defines hedge as “a particle, a word or phrase that modifies thedegree of membership of a predicate or a noun phrase in a set”. Although the threelinguists attempt to define the notion of hedges, it is not perfect to limit hedges toexpressions that signal the match between a piece of knowledge and a category(Markkanen & Schroder, 1997).Due to the rise of pragmatics in the 1980s, the definition of hedges begins to goaway from its origin of logics and semantics. Fraser (1980) confines hedges to theexpressions like sort of, kind of , which mitigate the harshness and hostility of theforce of one’s action. Coates and Cameron (1988:113) treat hedges as “those linguisticforms which are used to indicate the speaker’s confidence or lack of confidence in thetruth of the proposition expressed in the utterance”. Crystal (1997) refers to hedges aslinguistic items that express a notion of impression and qualification. Hyland (2004)argues that hedges, such as possible, might and perhaps, imply explicit qualificationof writer’s commitment.

………….

2.2 Research on scientific hedges abroad

As the increasing influence of pragmatics in the 1980s, research on hedges hasgradually stepped into the domain of pragmatics where these phenomena are closelyrelated to the concepts like politeness (Brown & Levinson,1987; Fraser, 1980;Myers,1989; Holmes,1993; Panther, 1981), mitigation (Fraser, 1980), vagueness(Channell,1994; Zuck & Zuck,1987) and modality (Stubbs, 1986; Preisler, 1986 ).Most of these studies focus on hedges or hedging in spoken discourse. Subsequently,based on the findings from spoken texts, linguists begin to study hedges in writtendiscourse, especially in academic texts. Speech act theorists show great interest in hedging devices for which implywriters’ intentions in performing illocutionary force on speech acts. Panther (1981)puts forward the notion of hedged performatives, which are used by scientific writersto perform indirect speech acts to establish an objective image of themselves. Withreference to Panther’ hedged performatives, Hyland (1998a) argues that scientifichedges serve both communicative and interactive function. On the one hand, writersuse hedged performatives to signal their belief in the truthfulness of the propositions;on the other hand, such performatives create a condition to persuade readers to accepttheir claims.

………

Chapter Three Theoretical Framework......... 18

3.1 Scientific claims in constructing knowledge........18

3.2 Verschueren’s theory of linguistic adaption.........19

3.3 Summary...... 26

Chapter Four Methodology......27

4.1 Research questions.....27

4.2 Data collection.....27

4.2.1 Criteria for data collection....27

4.2.2 Sampling procedures.....28

4.3 Identification of hedges.....29

4.4 Analytical procedure.........30

Chapter Five Adaption Approach to Hedges in SRA Introductions.......32

5.1 General statistics of hedges......32

5.2 The use of hedges — a process of making choices.....33

5.3 The use of hedges — a means of adaption to the communicative context.... 49

5.4 Summary...... 59

Chapter Five Adaption Approach to Hedges in SRAIntroductions

5.1 General statistics of hedges

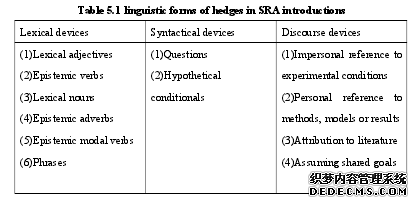

Hedges in our corpus appear over 12 times every 1000 words. There are 432hedges among 34860 words, which are realized on the level of lexical, syntactical anddiscourse structure. To be specific, lexical hedges include lexical adjectives, epistemicverbs, nouns, adverbs, modal verbs and phrases. In terms of syntactic structure,linguistic hedges are questions and hypothetical conditionals. Discourse devices areessentially Hyland’s (1998a) strategic hedges, which are implicated by the semanticstructure of the whole utterance (Yang, 2001). In our journal corpus, such devices arecomposed of attribution to literature, assuming shared goals, personal and impersonalreference. These linguistic forms are listed as follows: The above pie chart reflects the overwhelming distribution of lexical mitigationin our corpus, covering a high proportion of 90.28%, whereas syntactical just accountfor 3.24% and discourse devices for 6.48%. Such disproportional phenomenon inamount indicates that in the introduction of SRAs, hedges are mainly realized in theform of lexicon rather than syntactical and discourse pattern.

………

Conclusion

This section sums up the research findings concerning the use of scientifichedges in introduction sections. We mainly focus on three aspects:(1) the forms ofhedges in our corpus; (2) the dimensions involved in choosing hedges; (3) thecontextual correlates motivating the choice.First, in the analyzed 40 SRA introductions, hedges appear over 12 times every1000 words. There are 432 hedges among 34860 words in total. In terms of linguisticforms, hedges are realized in lexical, syntactic and discourse version. Lexical hedgesaccount for 90.28%, including lexical verbs, lexical adverbs, lexical adjectives,epistemic model verbs, epistemic nouns, lexical quantifiers and phrases. Comparedwith lexical hedges, syntactical and discourse devices are disadvantaged in number.The former only covers 3.24%, comprising questions and hypothetical conditionals.The latter’s proportion is 6.48%, containing personal and impersonal reference,attribution to literature as well as assuming shared goals. The predominant amount oflexical forms corresponds to the routine lexical devices employed in mitigatingmeanings. As a result, compared with syntactic and discourse hedges, English writersare inclined to choose lexical forms to express tentativeness and possibility.

…………

Reference (omitted)